Memory, loss, dreams, and isolation—these are just a few themes that game designer, artist, and producer Nick Murray seeks to address. While these are heavy subjects, Nick’s work carries a levity to its form—whether it’s through a Tamagotchi seance or a magical analog telephone. This makes for an emotional depth that captures what it is to be human in a world mediated by the digital. With a background in poetry publishing in performance and music composition, the London-based creative also serves as a producer for Now Play This, an experimental games festival.

Here, we speak with Nick about his practice that ties together his passion for poetry, music, and games. We also speak with Nick about the immediacy of an interactive narrative experience, an immediacy that feels similar to witnessing a live performance.

Could you talk about your upbringing? Was there a specific moment when you knew you wanted to do something creative in your life?

I’m London born and bred. My parents are immigrants to London; I’m first generation here. There was always a filter of discovery that came secondhand through my mom, specifically of feeling out what the city is like through her stories and reinterpreting that as I grew up.

I’ve been creative from a very young age. I started out playing classical music really young; I was trained in violin and viola. As I got older, I was a precocious teenager. I decided that that was too stifling and wanted to try something else. My teens led to performance and sound art. I started collecting art forms and was doing a bit of everything. They’ve all stacked on top of each other over the last 15 years to become interactive art. It feels like the natural culmination of all of these other things. Performance, digital art, poetry—it’s all part and parcel of the same thing, which at the moment, my medium has become interactive arts and games.

When I was exceptionally young, I remember being fascinated by the violinist Joshua Bell—he seemed like a really approachable person and cool and played what is traditionally quite a stifled or stuffy medium. That led me down this route of wanting to play and share music with other people.

A huge influence is the poet Ross Sutherland, who straddles both page and performance poetry. Often, his work is about the nature of digital connections and how the world can be mediated through the digital interfaces we have now. Often, it’s serious. Sometimes, it’s really playful. It was one of the first instances I saw where poetry could then come into this unique space that I’ve never seen before.

All through this, I was playing games, but it took quite a while to discover the indie and art game scene. When I was younger, the closest thing to that was the demo scene. I got into this idea of people creating these little demos and sharing them around. It’s not necessarily an interactive thing; it’s a showcase of skill. That wasn’t something I wanted to pursue myself. My inspirations are highly performative artists instead of interactive artists up until last, six, seven years when I’ve been doing this kind of thing. It’s really broadened out to the interactive and art game scene.

Was there something about the form of poetry, like the line breaks, or how that text is scattered on the page, that made you want to carry it over into a new medium?

Previously, I was working in poetry publishing. I was working with a publisher called Penned in the Margins. A big part of my job was live literature and the performance of poetry. There’s so much that can be done with the form on the page. There’s a bit more interactivity if there’s someone performing in front of you—the immediacy of a person in front of you, even if you’re in the audience and you’re not actively reacting, or you’re not invited to do things that change the performance…it’s still interactive. There is a passive interaction in any kind of performance. That still is fascinating to me, the idea that interaction can come in so many of these different levels.

That’s when I started going into interactive poetry. I spent a few years doing my own performance work, which was very text-based but very physical, real-world. People sat down in front of me—it was really testing out the boundaries of where text and interactivity can be. It was also the start of instructional work—giving people instruction so that we’re creating aspects of this work that form a structure around where the work can go.

It sounds like your experience in publishing and as a musician coalesced into your current practice. Do you code your games yourself?

I have coded all of my games. It’s creative coding because I’m a bad coder. And so, it’s like whatever works. It’s very much duct tape and chewing gum on the back end. There were few very strictly interactive poetry or connected poetry pieces that are creative coding. There were definitely moments of dabbling with that code in the back end, just to see what could change and reiterating on these different little snippets of code and changing it around to see what could happen.

Some self-described creative coders talk about how the physical act of doing the coding almost feels like the act of performing. What does it feel like to be working on a game versus performing music? Are there similarities to the ways those two experiences feel?

There are definitely overlaps. If I’m performing music, it’s a lot more intuitive. There’s an element of letting it happen—just by the nature of having done it for so long. It’s muscle memory, feeling my way through it. With coding, it feels almost like a game in itself. I put these pieces together, see what will happen, and work through it like that. While coding is definitely fun for me to do, it is a means to an end.

Generally, how does a project come to fruition for you?

I’m always taking notes. It’s thinking a sentence is particularly interesting, or reading a book, or hearing a talk, and just pulling all of these bits together just so I can come back to them. It means that I end up having almost dozens of Post-Its, which I will push around to see the different connections between things and find interesting. We’ve all used a Notes app on our phones. Which is often interesting to come back to because I’ll quickly write something down and come back a week later and have no idea what it means. Maybe something interesting will come out of that.

I consider games to be a medium in the same way that painting or performance might be. I’ll start with the idea that I want to explore, and the nature of the interaction or the visuals will be almost secondary. I’ll flesh out an idea through the narrative or how I want it to be experienced. That might be as simple as I want people to feel a particular emotion. I’ll be trying to convey a particular emotion, and then a world expands out of that.

Coming from poetry and publishing, I was reading lots of poets and prose writers, and there was a moment when I suddenly realized that you’re given these emotions through a piece of work. There are many emotions that you can’t get in the same way if you’re not interacting. You can read a book, and you get excited because something amazing is happening, or you feel sad because a character died.

If you’re playing a game, you’re suddenly given access to things like guilt and pride. These emotions are around responsibility—as soon as you choose, the emotional palette changes from these passive emotions, where you’re emoting on behalf of someone else. As soon as you do it, you have to respond to your own choices. That’s where a lot of my games are coming from now, which is why a lot of them are bummers. I need to make a happy game at some point [laughs].

I would love to hear about how your analog phone-based project Dial 5555 came to be.

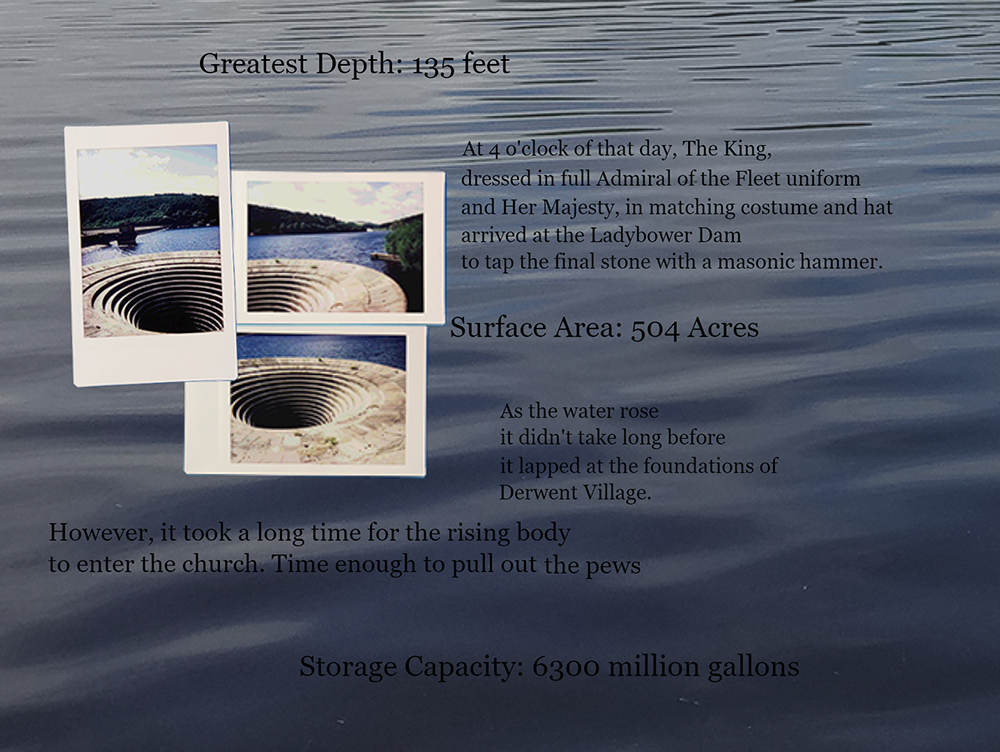

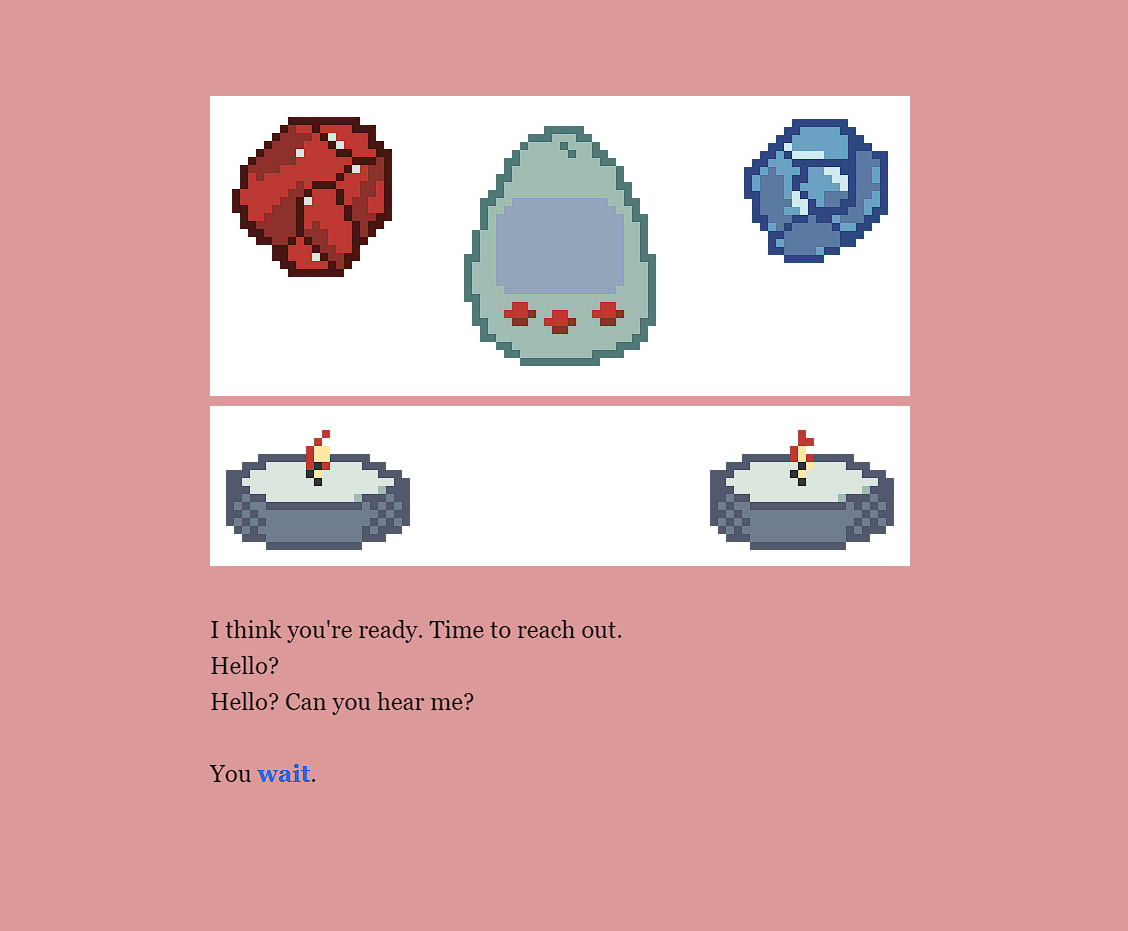

I designed this branching narrative piece that explores loss and grief in digital spaces. I was trying to work out how to give people something to latch onto in terms of this quite amorphous idea. That turned into a semi-physical location, or this almost dream location. You never get a definite answer as to whether it exists. But within the game, people are there. People live there.

At Now Play This Festival a couple of years ago, we decided to show the game Dream Phone. It’s this game from ’96—you have a big pink phone, and you have to dial your perfect dreamy, hunk boyfriend. With no hint of irony, I think that Dream Phone is perfectly designed to the point where I’m trying to make a spin-off version, my own fan version, called Dream Horse where you have to find your perfect horse.We were putting this out, and I got fascinated with the objectivity of it. The fact that there is a physical presence beyond the board… you’re playing a board game, but to all intents and purposes, it’s not really an object. It’s very flat. It’s essentially an image that you’re projecting something else onto.

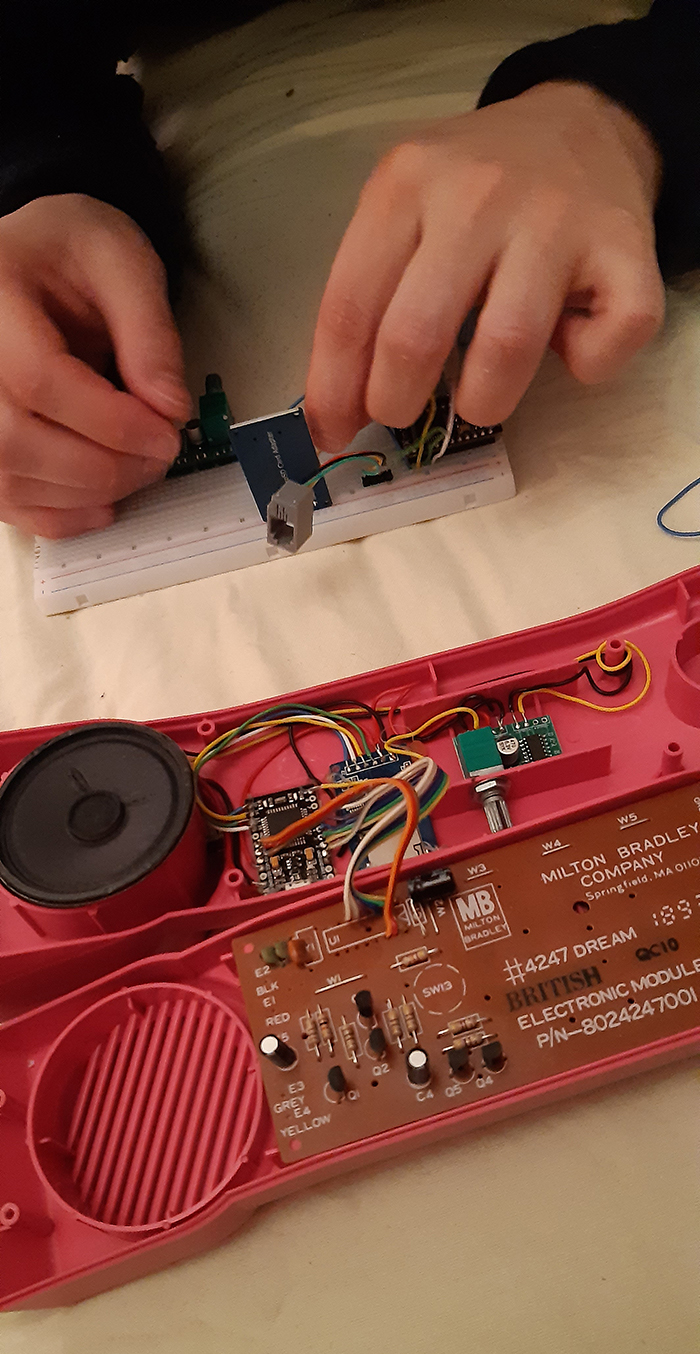

Dream Phone has this big old pink phone. It got me thinking about the idea of making the whole game housed within an object. The physicality of that really adds to the intimacy—it very much has started as an art project as opposed to a game that could go industry-wide. The idea that you know that only one person is playing this and having this experience in the world. You are dialing into this space that doesn’t quite exist. And so, I spent some time really looking into the physicality of that and bought a ton of phones, handsets, all these old 90s handsets. Turns out you can buy really cheap handsets on eBay. That was very useful. I was lucky at the tail end of 2019 to have a small grant from the Arts Council to explore the crossover of poetry and video games. And so, I was using some of that as a time to develop this game as well.

I was working out the physicality, whether it needed to be housed in something. At what point does this phone become real? Do I want it to become real? Because none of the numbers you dial are the real length of numbers. They’re all five digits because I thought that would be just easy for people to remember as you go along. I wanted the phone to look as real as possible. Once I do that, does it have to be plugged into a wall to feel real? How much of it had to be theatrical? I started thinking about whether it needed to be in a phone booth—that was far too much. I dialed it back down to just being a phone and then went back to the narrative and story going on inside.

This branching narrative follows six voices, one of which is an automated clock, like how you used to be able to dial in and have the time be told to you. That evolves into all these strange dreamscape poems told through the voice of this clock. A shopping channel, you can dial up a shopping channel that gives you these hints of this world. The others live either in the city or in a neighborhood nearby. You get snippets of how these people are either bolstered or ground down by their surroundings; why they might want to shift to another.

Through these different narratives that you get by literally dialing numbers that you’re told through these messages, I hope that the player starts to get this sense of almost a kind of melancholy. I’m trying to tow this line between dreamy in a very almost dream-pop sense, use musical stuff, and more poetic melancholy. What connects all the characters, including the clock and the shopping channel, is that they all talk about loss. Throughout eight or nine messages, every one of them explores a different aspect of loss and how they deal with it in a world where they can’t quite connect.

I started making a digital version that you could access just on your phone, on your mobile phone, but it doesn’t quite do the same thing. I found that it doesn’t have to be all audio now. There are moments where the same story suddenly breaks off, and you have a text-based game come up, or something that looks a bit like Snake—but you can’t move the snake, and that’s very frustrating, but purposefully so. It’s split off into these two different worlds that I now have to work out which one is more important in telling the story.

It almost has this David Lynch feel to it.

That’s very high praise.

This feeling of mystery or loss—someone entering a space or returning to space and not really knowing what the change is or discovering what the change over time has been as you go on in the story.

I love the idea of mystery, but in the sense that you could end a mystery and find your own answer. That’s just as satisfying as someone else’s answer, which might be completely different. You don’t have to reach a concrete goal. Spoiler alert, there’s definitely not going to be a happy ending at the end of Dial 5555. Even if it’s not happy, it’s satisfactory. You can reach the end, and put the phone down, and then feel like you’ve taken in enough of these people’s lives to feel like it was worth it.

I’m curious about the narrative design process for Dial 55555. Earlier, you spoke about Post-It notes as a nonlinear way of organizing.

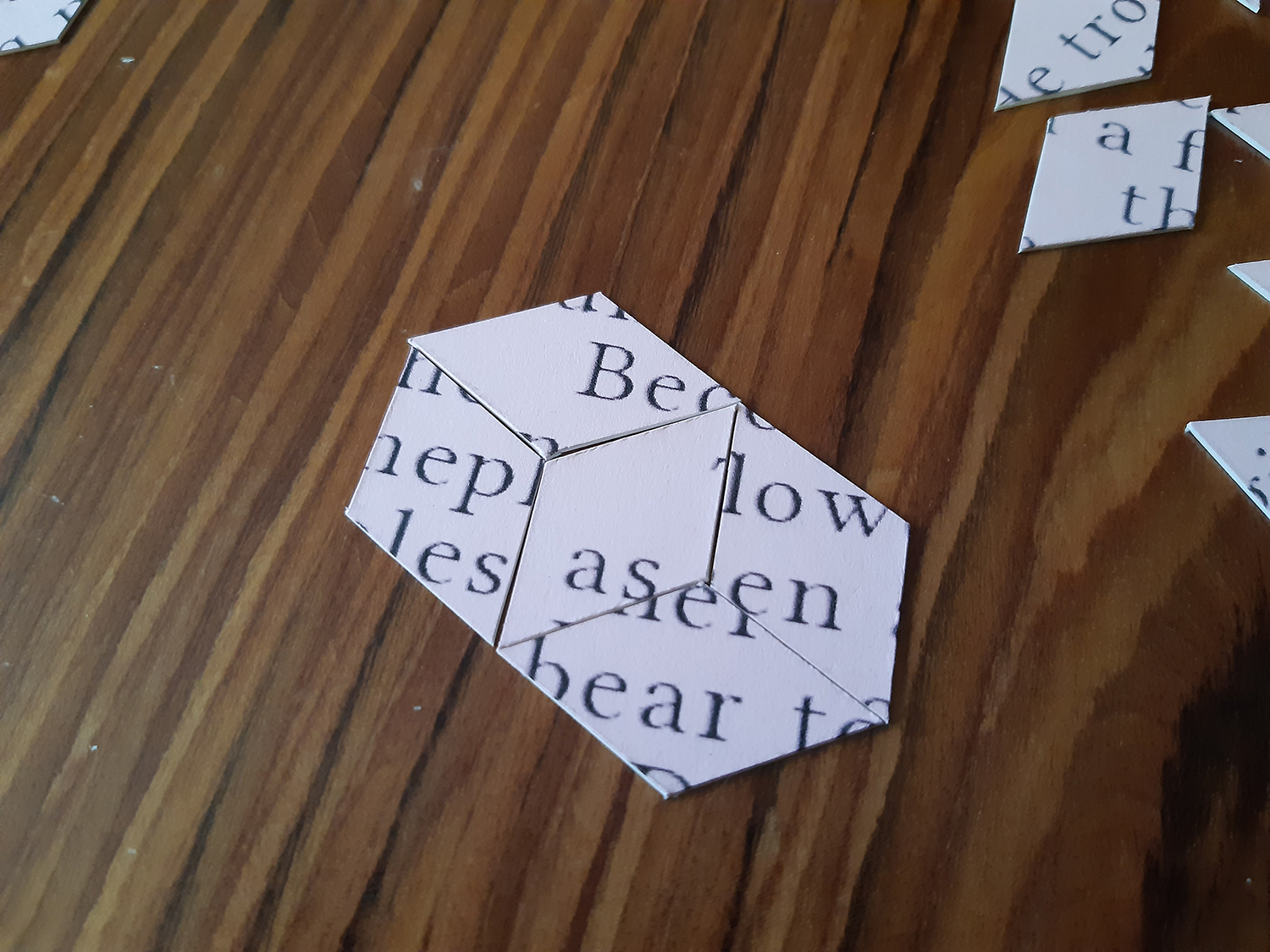

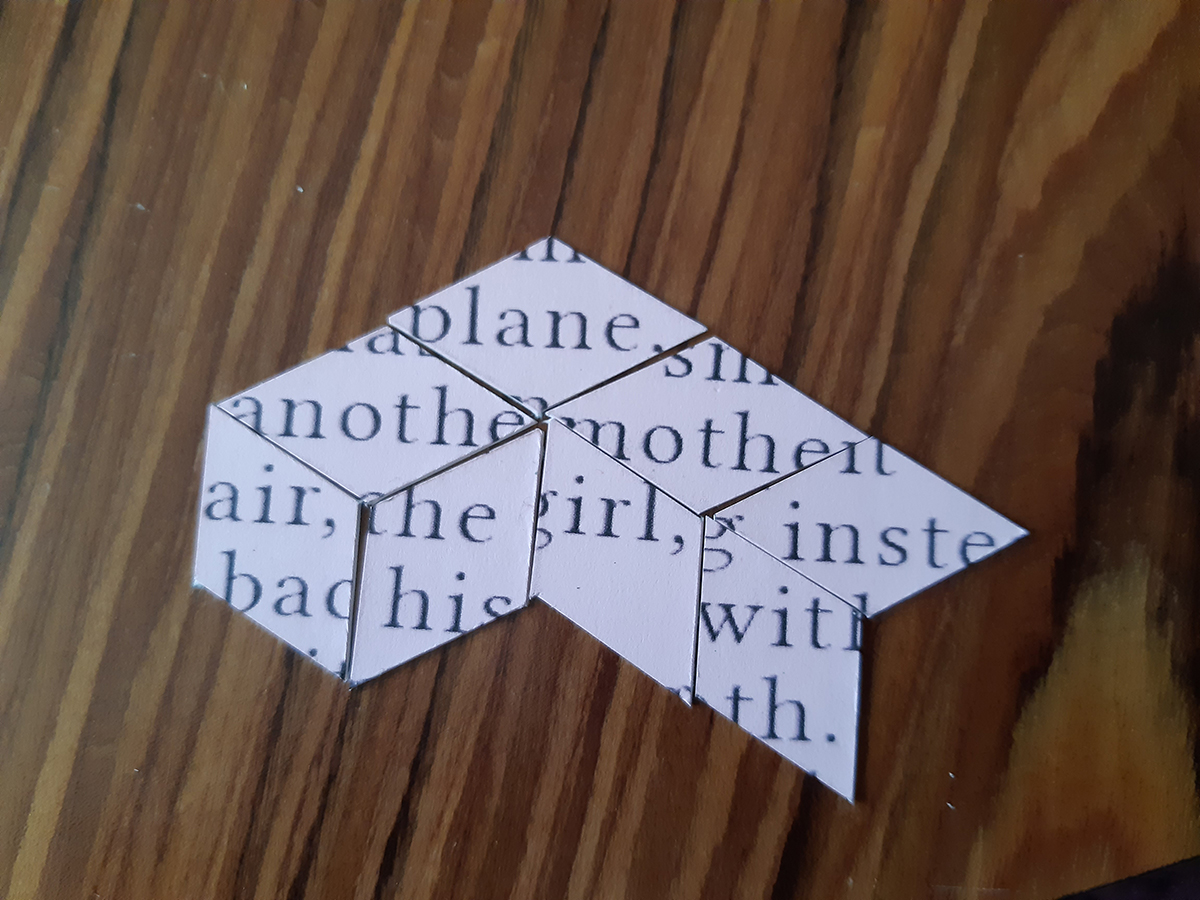

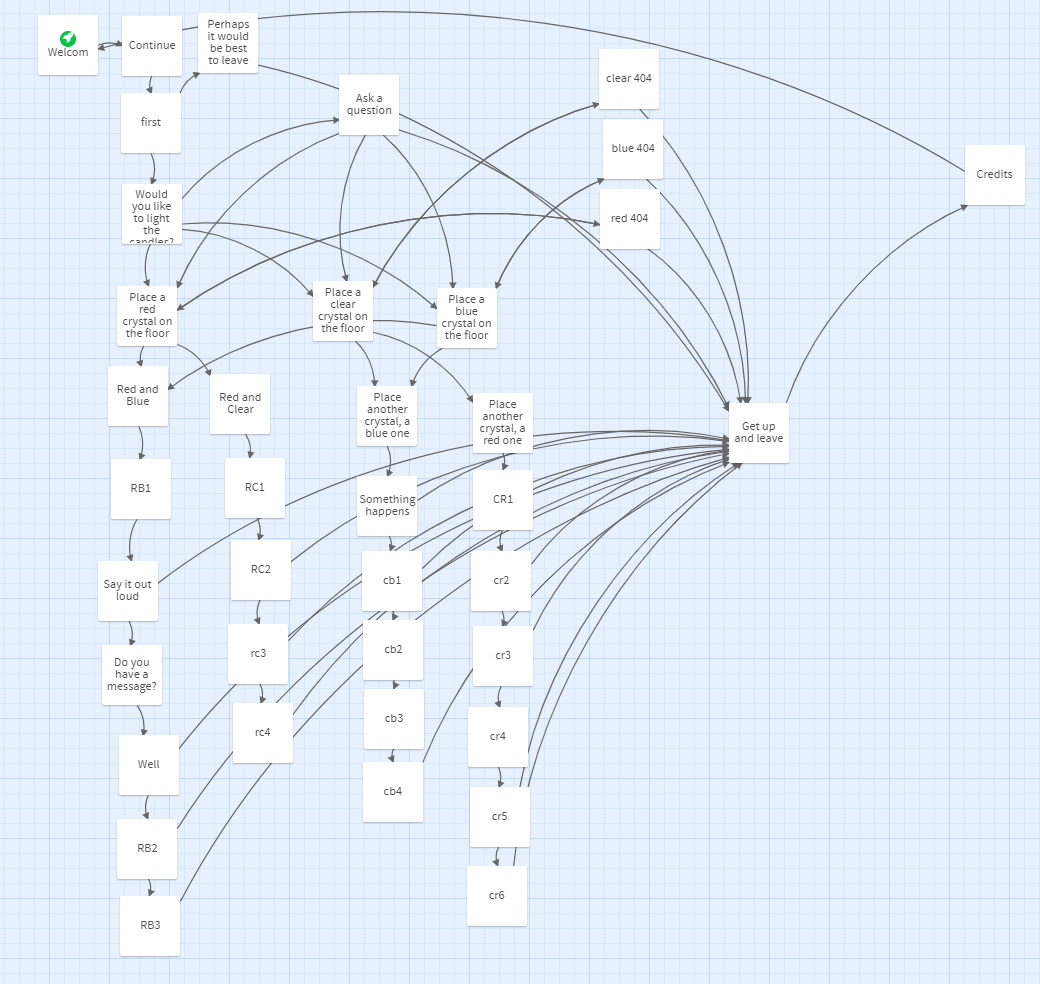

I put the whole story into Twine, a text-based game engine. Twine is brilliant for particular things but actually trying to work something out, it doesn’t quite have that workflow. So I’ve tried other things online. I realized that I just made Post-It notes again! I had just made digital Post-It notes and turned the computer off. So, went back to literal Post-It notes on the wall just spread out because the narrative of Dial 5, Even though it’s a branching narrative can still have linear moments, like you’re going from A to B to C. But within this game, you don’t have to do that. You can start with any particular character and jump between them in different orders. It’s not chronological. To an extent, it’s not topographical either. There, you can go to different places at the same time.

I needed to be able to physically do that in writing the narrative. Having a very physical medium was essential, just putting things in different places and seeing how it felt to me to be able to take those journeys. If I were to give unsolicited advice to anybody, it would be to do everything… If you’re making games, don’t make them on the computer to start with. You can spend so long choosing the right tool, and actually, that can be just such a hindrance. Just work out what it is, or play around with what it is you want to do. And then, try and make it. We have all of the tools to make perfect games at our fingertips always, and then you can just make those more colorful or have some nice melodies and things like that once you’ve taken it into another space.

As a producer for the game festival Now Play This, I imagine a lot of the work is curatorial. How has the exposure to game artists have filtered into your creative practice?

I feel so intensely privileged to have access to all of these incredible artists, writers, producers, just people interested in furthering this particular discourse around games as a medium for expression, for, yeah, unique and innovative expression. If we’re exhibiting an artist, there’s a whole dialogue around how and what that should look like—the experience of coming into an exhibition space and then being presented with a game. That’s a real special moment. There’s something really tangible in that that is not the same when you’re at home.

Anyone can turn on their computer and access a game and play it. That’s a beautiful thing in itself. You can take in a story. If you’re coming to an exhibition space, something happens at the front door where the world changes, and you’re now giving yourself rules for that world that you need to follow for whatever’s going on. We’d have wonderful moments of creating these cabinets or custom controllers for particular games and thinking about the placement in between other games, and what relates to each other, and how long we want people to stay in a room.

A couple of years ago, we had a game called Malapropic Karaoke in which an AI re-presented karaoke tracks but with nonsense words. It’s a really wonderful piece. It came to us housed in a little arcade box. That was great, but we really wanted to push the fact that karaoke is this amazing party moment. Karaoke is a great leveler. And so, we ended up fully tinseling an entire room, and getting disco balls in. It was a massive hit. It felt really silly to do it, but actually, every step of it was the right choice. Every time I would walk past, people were having the greatest time singing the most nonsense. That was brilliant.

It’s little things like that that really have helped with my own practice as well, to be able to help other artists in terms of their platforms, both digital and physical, and really explore that physicality of what playing games in a space that’s public or a space that’s not yours is. Even in the online festivals, we’ve had to go fully online in the last two years, this year and last year. There are moments where, if we’re streaming something, say on Twitch, there’ll be some artists who suddenly break off and have this huge chat in the Twitch chat that turns into a further reading or extra studies on the games that we’re playing and how they can be enriched. Now Play This has allowed me into a far wider discourse of games that I definitely didn’t have before. Hopefully, I’m contributing to it, too. It’s a huge back and forth.

What are you working on currently?

I really took the lockdown of being stuck indoors to actually take a moment to make some longer pieces that wouldn’t come out for a while. It’s what my entire practice is, but this idea of isolation, and grief, and loss in specifically in terms of the internet how digital cultures changed how we do and don’t remember things… what we leave. The things that we take back in and the things that we put away. My games are all around that at the moment.

The thing I’m working on currently is this thing. The working title is The Falling Man Simulator. You are just falling through the cosmos. You pick up these stories from other people who might be falling. It’s very much a tale about suburban loneliness and isolation. With contemporary computers, people had almost rediscovered different aspects of loneliness that we didn’t really think about before, because we didn’t have to. Computers and a lot of computer communication were secondary when you knew you could leave the house and see your friends. Fingers crossed, that’s the end of the year. Everything I’m making has this installation aspect and a custom controller that goes along with it so that you’re in the game before it even starts.

Will you bring the Falling Man Simulator into physical space as well?

For games that have quite serious themes, I want to make them as comfortable as possible. The physical element of this will have an aspect of falling, but I somehow want that to be comfortable. I want to create custom seating where you are reclining, and you have very, easy-to-use controls under your palms, wherever they sit. Then, the room has dynamic lighting that changes with the game itself so that you feel as much as you can of the game. I don’t think that the falling itself needs to be scary. It’s not that kind of dream of falling where you know you’re going to stop. It’s that endless fall where you don’t really realize you’re falling anymore.

If you were to fall forever through the universe, there might not be points of reference, so you don’t know if you’re falling or don’t know the takeaway of that falling. It’s just happening around you. I’m trying to find a universal way to talk about just the lives we’re living right now. Without being melodramatic, I think we’ve all been falling for a year.